Returning to Oaxaca from Hierve el Agua

Hierve el Agua

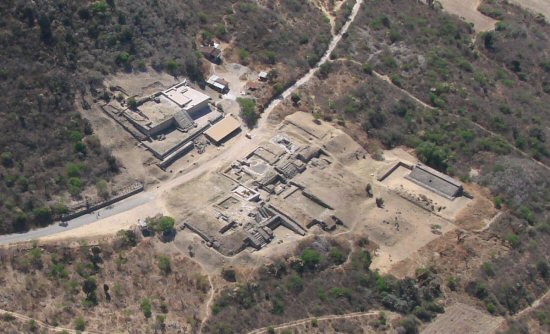

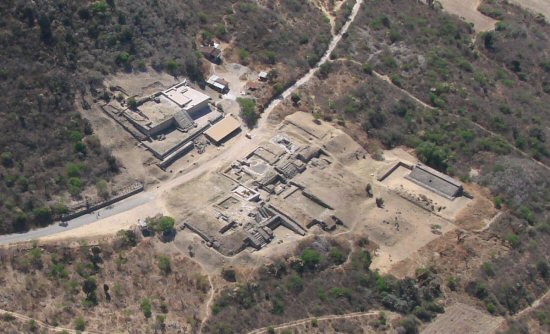

Archaeological site of Dainzu

Approach to Oaxaca

|

Returning to Oaxaca from Hierve el Agua

Hierve el Agua

Archaeological site of Dainzu

Approach to Oaxaca

|

Hierve el Agua is a site just above the central valleys of Oaxaca, at approximately 6,500 feet above sea level. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons it's passed up by the lion's share of tourists visiting Oaxaca. It consists of bubbling, mineral rich springs which feed two man-made pools suitable for a refreshing swim, and a couple of petrified "waterfalls," all located in an absolutely breathtaking mountain setting.

Tom Penick owns a popular website (tomzap.com) designed to assist travelers interested in learning about and visiting one of three states in Mexico which border on the Pacific; Jalisco, Colima and Oaxaca. While he gathers a lot of information about these states from third party sources, he likes to periodically update his website by personally visiting the regions where he has gained some expertise. For Tom's February, 2011, sojourn to Oaxaca, he was accompanied by his wife, Nancy, and spry, delightful, 96 - year - old mother, Doris.

My wife Arlene and I had decided to invite Tom and family over to the house for drinks and botanas, simply as a nice gesture, since as is the case with so many of us in the age of email, facebook and twitter (I must confess I abhor the latter two), I had come to know Tom and Nancy quite well over the past few years, but only online through advertising on tomzap.com, submitting articles to his website, and more generally as a consequence of passing on information about Oaxaca to Tom for publication.

Sometime in the course of that evening of chatting and indulging in food and drink with Tom and Doris (Nancy had been ill so could not join us), Arlene and me, and our friends Pilar Cabrera and Luis Espinosa (of La Olla restaurant and Casa de Los Sabores Cooking School), Arlene mentioned to Tom that I was hoping to accompany him to Hierve el Agua. I had not planned on broaching the topic that evening, even though I had mentioned to Tom in the course of emailing, that I would love to see the site from his plane.

As I was dropping off Mr. Zap and his mother at their hotel at the conclusion of our evening together, Tom said that the only day he would be able to take me to Hierve el Agua was Monday. "Tell me what time and I'll be by to pick you up and we can head to the airport," I replied excitedly.

The small Mexican domestic airlines which fly to and from Oaxaca and both Puerto Escondido and Huatulco (the two major Pacific coastal resorts in the state), Aerovega and Aerotucan, take off in the mornings, as early as 7 a.m., although at times weekend flights leave around noon. Wind currents over and between the mountains tend to pick up in the afternoon, and accordingly morning flights reduce the likelihood of significant turbulence and make for more comfortable and enjoyable flying. Tom suggested I come by for him at 8 a.m.

The Oaxaca airport is comprised of two terminals, the large one for international and domestic commercial jet air travel, generally used by planes which can accommodate at least 50 passengers; and the small one for the military, sometimes cargo, short haul runs by small airlines such as Aerovega and Aerotucan, and for small private planes. A perk of using the small terminal is that parking to pick up and drop off passengers and when you're off for a short flight in a private plane, is free. The air of informality is also pleasing, of course not extending to matters of safety and security.

With twenty years of flying experience under his belt, including several flights between home state Texas and Mexico, Tom knows the ropes, although his Spanish could use more work than mine. But when flying in Mexico you can get by with little Spanish, since air traffic controllers can communicate in English.

Doris and I waited for close to half an hour while Tom attended to the required paperwork and fee payment. We knew that he would have to walk from office to office, but at least the offices were in the same small terminal complex, not always the case.

A glitch arose, at which point I initially thought that we would not be permitted to take off. Tom returned from his final office visit, requesting my assistance as a Spanish speaker. "Alvin, I think I need your help; the guy upstairs says that foreigners are not allowed to just take off in a plane for a little sightseeing trip; you have to be going somewhere and land there."

I accompanied Tom to the upper deck, where we met with Juan, in apparent charge of such matters, and the one who had moments ago turned away Tom. I initially thought that flashing my permanent Mexican residency card would work since in many cases being a resident trumps the FM - 2 and FM - 3 visas which are held by most foreigners living in Mexico; but in this case it just wasn't good enough. I then asked if this was a rule specific to the state of Oaxaca, or just to this airport, but received no reply. I indicated that Capitán Tom had gone on similar short flights, up the coast leaving from both Puerto Escondido and Huatulco airports, always receiving the required stamped permission.

We were not prepared to take "no" for an answer, at least not so easily, so we held our ground until Juan said "then you'll have to speak to the comandante." While we walked across the hall I began fidgeting in my pocket, looked for a couple of bills, of denominations not too large. "This pilot wants to fly to Hierve el Agua and then come back, but I already told him our rules," Juan explained. I piped in, "yes, we just want to go out there for a little while, take some photographs of the beautiful scenery, and come right back."

My interchange with the comandante went something like this:

"No, no, no, you're not allowed to take photographs from up there without a permit."

"Okay, can we fill in a form and get a permit?"

"You have to go to Mexico City for such a permit."

"Well, what if we put our cameras in the car, can we then go?"

"I didn't say you have to put your cameras in the car, just that you're not allowed to take pictures from up there; do you know what I'm telling you? It's for reasons of national security."

"Okay, so you're saying that we can go to Hierve el Agua, but we simply cannot take any photographs."

"That's right; so Juan, take these two gentlemen back to your office and complete the paperwork please."

I didn't even have to take my hand out of my pocket, and the rule against foreigners going up for a short flight and returning, was never discussed with the comandante.

But Juan did not like the way the flight plan had been filled in by the official in the SENEAM office. He had printed the 25 nautical miles we would be flying, and the direction, and then in parentheses indicated Hierve el Agua. "The form must be completed again, omitting the words Hierve el Agua." Tom began to ask me if I would suggest to Juan that we simply cross out those three words and initial the change. I explained that here in Oaxaca, in almost all instances you cannot make changes to the face of any official or quasi - official document; initialling does not remedy a defect. Documents are king; they are sacred, have a life of their own, and must not be torn, altered, smudged.

Tom went to two of the offices he had previously attended, then returned to Juan and had a fresh flight plan stamped. We were ready. We went through security and the x - ray machine, just as one does in any commercial airport terminal. I had been in a private single engine plane only once before, close to 40 years ago, with a friend who took me for a ride over Lake Ontario. This time I knew to take a Dramamine, early morning flight or not.

For Tom, checking over the exterior of his Piper Arrow II before take - off is second to nature. For me, seeing him carefully examine every screw, wire, hinge, moving part, and fuel - related mechanism was comforting, especially in light of the fact that I had only met Tom once before, and knew little of his personality including any propensity for dangerous or carefree living. But with his dear old mother on board, I knew all would be fine, if not out of concern for me or our pilot himself, then certainly for Dorita.

Two federales approached, weapons in hand, to check over the paperwork as custom dictates. I asked if I could take photos of the plane and they said it was okay, somewhat of a surprise to both me and Tom. I told Tom I would not take photos from the air, since I did not want a problem in case my camera was checked upon our return. I value the privilege of being able to live in Mexico. Tom had an extra memory card, so he put the new one in his camera, the plan being to put the old one back upon our return so that in the event anyone asked to check his camera, no photos of the trip would appear.

Tom examined the control panel and the multitude of screens and switches in the cockpit, then checked it all again. He explained what a couple of the screens were, but it went in one ear and out the other, except I took note of the LED screen which seemed would be functioning like a GPS. The engine started like a charm, but then Tom realized he didn't have enough space to turn out of the parking area because of the plane in front of us; he turned off the motor: "I guess I'd better get out and push the plane so we can get out of here; and what a pity, since it started so easily, just like that."

After several exchanges in English with the air traffic controller, we were Hierve el Agua bound. I must admit that for me the somewhat wobbly ascent was a bit uncomfortable. I sat beside Tom, feeling a bit like a co-pilot, with my own steering wheel and foot pedals. Soon enough we were at cruising altitude, Tom and I communicating with our headsets and attached microphones in place, while Doris sat in back, quietly. As we ascended to cruising altitude, Tom began taking photos, or perhaps he was using the video mode. I didn't ask. Tom would frequently use his camera throughout our flight.

The GPS unit told us how many minutes until we reached Hierve el Agua. Tom had us on a course, but I knew from having driven to the site hundreds of times over the past 20 years, that we were a few degrees off. Tom was relying on his sophisticated navigational equipment, while I was simply looking down at the highway and dirt roads leading to Hierve el Agua; familiar landmarks including ruins, towns, particular restaurants and mezcal - producing facilities; and mountain peaks I had frequently criss-crossed in my pick - up or the van. There it was, Hierve el Agua in clear view as we flew over the final mountain top; the poolings of water, the falls, and the newly constructed yet abandoned modern brick buildings and large, concrete swimming pool (one of the white elephant's of the last governor's administration). Of course we could not see the water bubbling up from the ground, nor any tourists milling about, but all the rest was easily visible, even more so as we descended and circled twice.

"Those are all agave espadín fields under cultivation on the surrounding slopes, with pretty well no corn," I explained. There are a couple of towns close to Hierve el Agua, such as San Juan del Rio and San Lorenzo Albarradas, many of the residents of which are dedicated to producing mezcal the old - fashioned way, using firewood to bake the agave, a horse pulling a limestone wheel to crush it after it's been cooked, pine vats to ferment, and a brick, mud and copper still for the final stage of the process.

As we descended down into the valley as close as possible to the actual site, the wind took hold of us, making the ride rather bumpy, and my stomach more than a little queasy. As much as I was in awe with the experience, I secretly hoped that two circling downward swoops would be all, and that soon we'd be on our way back. I looked around near my feet, but could not find a bag in case my stomach decided to completely revolt, of course too embarrassed to ask if one existed.

I suggested a little more direct return route than we had used in arriving at Hierve el Agua. Tom complied. In due course we joined up with the main highway, #190, which we had been following for our arrival route. I pointed out Mitla, Dainzu, and the Armando Prieto massive, modern mezcal factory which produces the Zignum brand. We flew over a few housing developments I did not know existed because they were well set back and not visible from the main highway. There were also a couple of expansive green areas which were similarly unfamiliar to me. It was indeed rare to encounter them in the midst of the dry season. They appeared to be sod farms, but confirmation would have to await an exploratory drive through the countryside. Finally, we passed by the pre-Hispanic pictographs on a couple of rock facings, near Yagul, and at Xaagá just beyond Mitla, the two of which had contributed to the 2011 UNESCO designation of the area as a World Heritage Site.

Our landing was uneventful, except that on our approach Tom did a maneuver known as a "slip," a means of losing altitude more quickly without speeding up. We initially saw four white lights guiding us in. The appearance of two white and two red, is a guideline for a happy landing, indicating that the airplane is on a 3 degree glideslope to the touchdown zone of the runway. While I don't think Capitán Tom was aware of my earlier nausea, it was nevertheless kind of him to do whatever was appropriate to reasonably assure a smooth and uneventful return to mother earth.

By the time we had touched down, Tom had already switched his memory cards. No one asked to see our cameras, and we were not approached by federales after landing, a surprise for Tom. Tom asked airport personnel if there were any further steps to follow before leaving the terminal, and was told we could simply leave. Even for me it seemed unusual that Mexico would permit an airplane to land and park, and its occupants depart the premises, without any checking of anything, by anyone, regardless of the fact that less than an hour ago we had departed. Perhaps our every move had been monitored.

Virtually no tourist to Oaxaca, or resident for that matter, ever has a chance to view Hierve el Agua from an airplane. But those with any opportunity to get to the site the traditional means should not pass it up. Hierve el Agua is one of the premier wonders in all Oaxaca.

Alvin and Arlene Starkman operate Casa Machaya Oaxaca Bed & Breakfast. Alvin writes, takes couples and families to the sights in the central valleys of Oaxaca, and consults to documentary film companies. Alvin and Pilar Cabrera lead culinary tours in the Oaxaca through Oaxaca Culinary Tours (http://www.oaxacaculinarytours.com).